Useful Road Map for Employers to Conduct Direct Threat Analysis Under the ADA

Most employers are familiar with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and its requirement to provide reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities. There is less certainty about the extent of this obligation. For example, what if no reasonable accommodation could eliminate the danger—the "direct threat"—the individual poses in the workplace?

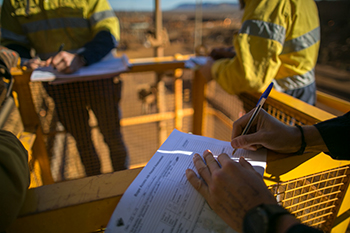

This was the scenario U.S. Steel confronted after it extended a conditional offer of employment to a job candidate to work as a Utility Person. Utility personnel are known as safety sensitive laborers, as these employees drive forklifts, work with power tools and torches, and work with or in the vicinity of hazardous chemicals and molten metal.

Following the conditional job offer, plaintiff was sent for a fitness-for-duty exam. During this process, the employer learned that plaintiff had a history of seizures and that he had stopped taking anti-seizure medication against his physician’s advice. While he had only had four seizures in his lifetime, there was no guarantee there would not be another one. Ultimately, the employer determined that plaintiff posed a direct threat to himself and those in the workplace, and his conditional offer of employment was rescinded.

Following the conditional job offer, plaintiff was sent for a fitness-for-duty exam. During this process, the employer learned that plaintiff had a history of seizures and that he had stopped taking anti-seizure medication against his physician’s advice. While he had only had four seizures in his lifetime, there was no guarantee there would not be another one. Ultimately, the employer determined that plaintiff posed a direct threat to himself and those in the workplace, and his conditional offer of employment was rescinded.

Plaintiff challenged the employer’s finding that he posed a direct threat in the workplace by filing a lawsuit for disability discrimination in the Northern District Court of Indiana against U.S. Steel. Ultimately, the district court granted a motion for summary judgment filed by U.S. Steel, and the Seventh Circuit affirmed. In doing so, the court identified what an employer must prove to establish a "direct threat" defense. Specifically, the employer must conduct an individualized assessment of the person’s ability to safely perform the essential job functions. Key factors in the analysis are (1) the duration of the risk; (2) the nature and severity of the potential harm; (3) the likelihood that the potential harm will occur; and (4) the imminence of the potential harm.

In its individualized assessment, U.S. Steel reviewed applicable DOT regulations, plaintiff’s completed health inventory form, a physical examination, and plaintiff’s medical records and neurologist’s notes. This assessment led to the conclusion that plaintiff’s disorder was not well controlled. Furthermore, instead of being of a limited duration, plaintiff’s disorder was of an indefinite nature. Given the safety-sensitive nature of the position, U.S. Steel concluded that the nature and severity of the potential harm would be disastrous as it was found that plaintiff’s seizures could cause him to lose consciousness. Likewise, the fact that plaintiff’s seizures were uncontrolled and of unlimited duration established the likelihood of potential harm. With respect to the last factor, the imminence of potential harm, this was a closer question as plaintiff only had four seizures in his lifetime. However, two of those episodes came after he stopped taking medication, supporting a finding that he was now at a higher risk of having a seizure. Weighing all these factors, the court concluded that U.S. Steel’s decision to rescind his job offer—because he constituted a threat to himself and others—was proper.

This case provides a useful road map for employers to make their own direct threat determinations. Paramount to the process is an individualized analysis of the applicant’s ability to safely do their job. A medical examination of the applicant along with the consideration of relevant medical records is crucial when weighing the four direct threat factors. Employers must document everything that is done to evaluate the employee, his/her present ability, the requirements of the job, and the likelihood and probability of the harm that could occur in the workplace. Additionally, employers should keep the applicant apprised of the analysis, seeking his/her input, while continuing to recognize that the direct threat analysis and decision remains at all times with the employer. See, Pontinen v. U.S. Steel Corp., 18-cv-232 (7th Cir. Feb. 11, 2022).

Topics

- #12Days

- #MeToo

- 100% Healed Policy

- 12 Days of 2024

- 2015 Inflation Adjustment Act

- 24-Hour Shifts

- Abuse

- ACA

- Accommodation

- ADA

- ADAAA

- ADEA

- Administrative Exemption

- Administrative Warrant

- Adverse Employment Action

- Affirmative Action

- Affordable Care Act

- Age Discrimination

- Age-Based Harassment

- AHCA

- Aiding and Abetting

- AMD

- American Arbitration Association

- American Health Care Act

- American Rescue Plan

- Americans with Disabilities Act

- Amusement Parks

- Anti-Discrimination Policy

- Anti-Harassment

- Anti-Harassment Policy

- Anti-Retaliation Rule

- Anxiety

- Arbitration

- Arbitration Agreement

- Arbitration Fees

- Arbitration Rule

- Arrest Record

- At-Will Employment

- Attorney Fees

- Attorney General Guidance

- Audit

- Automobile Sales Exemption

- Baby Boomers

- Back Pay

- Background Checks

- Ban the Box

- Bankruptcy

- Bankruptcy Code

- Bargaining

- Bargaining Unit

- Baseball

- Benefits

- Bereavement

- Biden Administration

- Biometric Information

- Biometric Information Privacy Act

- Black Lives Matter

- Blocking Charge Policy

- Blue Pencil Doctrine

- Board of Directors

- Borello Test

- Breastfeeding

- Browning-Ferris

- Burden of Proof

- Burden Shifting

- But-For Causation

- Cal/OSHA

- California

- California Administrative Procedure Act

- California Consumer Privacy Act

- California Court of Appeal

- California Department of Fair Employment and Housing

- California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement

- California Fair Employment and Housing Act

- California Family Rights Act

- California Labor Code

- California Legislature

- California Minimum Wage

- California Senate Bill 826

- California Supreme Court

- Call Centers

- CARES Act

- Case Updates

- Cat's Paw

- CCPA

- CDC

- Centers for Disease Control

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- CFAA

- Chicago Minimum Wage

- Child Labor Laws

- Childbirth

- Choice of Law

- Church Plans

- Circuit Split

- City of Los Angeles CA Minimum Wage

- Civil Penalties

- Civil Rights

- Civil Rights Act

- Claim for Compensation

- Class Action

- Class Action Waiver

- Class Arbitration

- Class Certification

- Class Waiver

- CMS

- Code of Conduct

- Collective Action

- Collective Bargaining

- Collective Bargaining Agreements

- Collective Bargaining Freedom Act

- Committee on Special Education

- common law

- Commuting Time

- Comparable Work

- Compensable Time

- Compensation History

- Complaints

- Compliance

- Compliance Audit

- Computer Exemption

- Confidential Information

- Confidentiality

- Confidentiality Agreement

- Constructive Discharge

- Consular Report of Birth Abroad

- Contraception Services

- Contraceptive

- Contracts Clause

- Conviction Record

- Convincing Mosaic

- Cook County

- Cook County Minimum Wage

- Coronavirus

- Corporate Board

- Corporate Compliance

- COVID-19

- Criminal Conviction

- Criminal History

- CSE

- Customer Service

- D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals

- DACA

- Damages

- Deadline Extension

- Defamation

- Defendant Trade Secrets Act of 2016

- Delaware

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of Economic Opportunity

- Department of Industrial Relations

- Department of Justice

- Department of Workforce Development

- Designation Notice

- DFEH

- DHHS

- Direct and Immediate

- Disability

- Disability and Medical Leave

- Disability Discrimination

- Disability-Based Harassment

- Disciplinary Decisions

- Disclosure

- Discrimination

- Disparaging

- Disparate Impact

- Disparate Treatment

- District of Columbia

- Diversity

- Diversity Policy

- Documentation

- Dodd-Frank

- Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

- DOJ

- DOL

- Domestic Violence

- DOT

- Drug Free Workplace Act

- Drug Free Workplace Policies

- Drug Testing

- Dues

- Duluth

- DWD

- E-Verify

- EAP Exemption

- Earned Sick and Safe time

- Eavesdropping

- Education

- EEO Laws

- EEO-1

- Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

- El Cerrito CA Minimum Wage

- Election

- Electronic Communication Policy

- Electronic Communications

- Electronic Monitoring

- Electronic Reporting

- Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals

- emergency condition

- Emeryville CA Minimum Wage

- Emotional Distress

- Employee

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Classification

- Employee Handbook

- Employee Information

- Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974

- Employee Termination

- Employer

- Employer Health Care Plans

- Employer Mandate

- Employer Policies

- Employer Policy

- Employer Sponsored

- Employer-Employee Relationship

- Employer-Sponsored Visas

- Employment

- Employment and Training Administration

- Employment Contract

- Employment Verification

- Enterprise Coverage

- EPA

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)

- Equal Pay Act

- Equal Pay for Equal Work

- Equal Protection

- Equality

- ERISA

- Essential Employment Terms

- Essential Functions

- ESST

- Ethnic Equality

- Evidentiary Burdens

- Exclusive Remedy

- Executive Exemption

- Executive Order

- Exempt Employee

- Exempt Status

- Exemption

- Experience

- Expert

- Expression of Milk

- Extreme or Outrageous

- FAA

- Failure to Accomodate

- Fair Credit Reporting Act

- Fair Employment and Housing Act

- Fair Labor Standards Act

- Fair Pay

- Fair Reading

- Fair Workweek Law

- Fair Workweek laws

- Families First Coronavirus Response Act

- Family and Medical Leave

- Family and Medical Leave Act

- family planning

- Fast Food

- FCRA

- FDA

- Federal

- Federal Arbitration Act

- Federal Drug Administration

- Federal Government

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation

- Federal Preemption

- Federal Register

- Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

- Federal Trade Commission

- Fee Disputes

- FEHA

- fertility

- FFCRA

- Fiduciary

- Fiduciary Duty

- Fiduciary Rule

- Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals

- Final Rule

- Fines

- fingerprints

- First Amendment

- First Circuit Court of Appeals

- Flexible Spending Accounts

- Florida

- Florida Civil Rights Act

- Florida's Private Whistleblower Act

- FLSA

- FLSA Exemptions

- Flu Shot

- Fluctuating Workweek

- FMCSA

- FMLA

- FMLA Abuse

- FMLA Interference

- Food Delivery

- Form 300A

- Forum-Selection Clause

- Fourteenth Amendment

- Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals

- Franchisee

- Franchising

- Franchisor

- Fraud

- Freedom of Speech

- FSA

- FTC

- Full-time hours

- garden leave clause

- Gay Rights

- Gender Bias

- Gender Discrimination

- Gender Equality

- Gender Identity

- Gender Identity Discrimination

- Gender Identity-Based Harassment

- Gender Nonconformity

- Generation Z

- Generational Conflict

- Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act

- Georgia

- Gig Economy

- Gig Worker

- Good Faith

- Graduate Students

- Grievances

- Grocers

- Gross

- H-1B

- Hair Discrimination

- Handicap Discrimination

- Harassment

- Hawkins-Slater Medical Marijuana Act

- Health and Safety

- Health Care

- Health Care Employers

- Health Care Provider

- Health Insurance

- HHS

- Highly Compensated Employees

- HIPAA

- Hiring

- Hiring Policy

- Hiring Practices

- HIV

- Hostile Work Environment

- Hour Tracking

- Hours Worked

- HR

- Human Trafficking

- Hybrand

- I-9

- IDHR

- IEP

- IHRA

- Illinois

- Illinois Business Corporation Act

- Illinois Department of Human Rights

- Illinois Equal Pay Act

- Illinois Freedom to Work Act

- Illinois Human Rights Act

- Illinois Minimum Wage Law

- Illinois Nursing Mothers in the Workplace Act

- Illinois One Day Off In Seven Act

- Illinois Supreme Court

- Illinois Workplace Transparency Act

- Immigration

- Impaired

- Impairment

- Incentives

- inclusion

- Income Tax

- independent contractor classification

- Independent Contractors

- Indiana

- Indiana Supreme Court

- Individualized Education Program

- informed consent

- Injuctive Relief

- Injunction

- Injuries

- Injury and Illness Reporting

- Interactive Process

- Interference

- Intermittent Leave

- Internal Applicants

- Internal Complaints

- Internal Revenue Service

- Interns

- Internships

- Investigation

- Iraq

- Iris Scans

- IRS

- IRS Notice 1036

- ISERRA

- IWTA

- janitorial

- Jefferson Standard

- Job Applicant

- Job Applicant Information

- Job Classification

- Job Classification Audit

- Job Descriptions

- Joint Control

- Joint Employer Relationship

- Joint Employer Rule

- Joint Employer Test

- Joint Employers

- Joint Employment

- Judicial Estoppel

- LAB s. 226.2

- Labor and Employment

- Labor Code

- Labor Dispute

- Labor Organizing

- Lactation Accommodations

- Lactation Policies

- Las Vegas

- lateral transfer

- Layoff

- Leased Employee

- Leave

- Ledbetter Act

- Legislation

- LGBTQ

- LGBTQ Rights

- LMRA

- Loan Forgiveness

- Local Ordinance

- Los Angeles County CA Minimum Wage

- Loss of Consortium

- M.G.L. Chapter 151B

- Major League Baseball

- major life activity

- Malibu CA Minimum Wage

- Mandatory

- Mandatory Arbitration

- Mandatory Reporting

- Manufacturers

- Marijuana

- Marital Discrimination

- Maryland Minimum Wage

- Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Equal Pay Act

- Massachusetts Pregnant Workers Fairness Act

- Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

- Massachusetts Wage Act

- Maternity Leave

- McDonnell Douglas

- Meal & Rest Break

- Meal Breaks

- Meal Period

- Media Mention

- Medical Condition

- Medical Examination

- Medical History

- Medical Marijuana

- MEPA

- MHRA

- Michigan

- Micro-Units

- Military

- Military Duty

- Millennials

- Milpitas CA Minimum Wage

- Minimum Wage

- Ministerial Exception

- Minneapolis Minimum Wage

- Minneapolis Sick and Safe Time ordinance

- Minnesota

- Minnesota Court of Appeals

- Minnesota Human Rights Act

- Minor Employees

- Minors

- Misappropriation

- Misclassification

- Missouri

- MLB

- Montana Human Rights Act

- Montgomery County Maryland Minimum Wage

- Municipalities

- Narrow Construction

- National Football League

- National Labor Relations Act (NLRA)

- National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)

- National Origin Discrimination

- Natural Hair

- Nebraska

- Negligence

- Neutrality Agreement

- New Jersey

- New Jersey Compassionate Use Medical Marijuana Act

- New Jersey Law Against Discrimination

- New Moms

- New York

- New York Average Weekly Wage

- New York City

- New York City Human Rights Law

- New York Court of Appeals

- New York HERO Act

- New York Labor Law

- New York Legislation

- New York Minimum Wage

- New York Paid Family Leave

- New York State Human Rights Law

- News

- NFL

- Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

- NJ DOL

- NJ Paid Sick Leave Law

- NJLAD

- NLRA Section 7

- No Rehire Provisions

- Non-Compete

- Non-Employee Union Agents

- Non-Supervisory Employees

- Noncompete Covenant

- Noncompetition Agreement

- Nondiscretionary Bonuses

- nonproductive time

- Nonsolicitation Covenant

- Notice

- Notice of Proposed Rule Making

- Notices

- NPRM

- Nursing Mothers

- NY State Department of Taxation

- NYSHRL

- Obama Administration

- ObamaCare

- Obesity

- Objectively Offensive

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- OFCCP

- Off-Duty Rest

- Off-the-Clock

- Office of Management and Budget

- Ohio

- Ok Boomer

- Oklahoma

- Older Workers

- OMB

- On-Call Scheduling

- Only When Rule

- Opinion

- Opinion Letter

- Opioid Epidemic

- Opposition

- Oregon Minimum Wage

- Organ Donation

- OSH Act

- OSHA

- Other-than-Serious Violation

- Outside Applicants

- Outside Sales Exemption

- Overtime

- Paid Leave

- Paid Sick Leave

- Paid Sick Leave Law

- Paid Time Off

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance

- Parental Leave

- part-time hours

- Partnership

- Pasadena CA Minimum Wage

- Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act of 2009

- Pay Data

- Pay Equity

- Pay Gap

- Pay History

- Pay Inquiries

- Paycheck Protection Program

- Payment Disclosure

- Payroll

- Payroll Taxes

- PDA

- Penalties

- Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania Minimum Wage Act

- Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Law

- Pension

- Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation

- Pension Plans

- Pensions

- Perceived Disability

- Permanent Replacement Employees

- Personal Protective Equipment

- Personnel Record

- PFL

- Physiological Condition

- Picket

- Piece-rate

- Policies

- Policy

- Political Affiliation

- Political Discrimination

- Political Speech

- Politics

- Polygraph

- Portland Maine Minimum Wage

- Posting Requirements

- PPE

- Preemption

- Pregnancy Discrimination

- Pregnancy Discrimination Act

- Pregnant Worker Fairness Act

- Pregnant Worker Protections

- Premium Wage

- Prescriptions

- President Obama

- Presidential Election

- Pretext

- Preventative Care

- Privacy

- Private Attorneys General Act of 2004

- Private Colleges and Universities

- Private Employers

- Private Property

- Professional Exemption

- Property Rights

- Proposed Rulemaking

- Protected Activity

- Protected Class

- Protected Concerted Activity

- Protected Leave

- Protected Speech

- PTO

- PTSD

- Public Employers

- Public Records

- Publicly-Held Corporations

- PUMP Act

- Punitive Damages

- qualified individual

- Qualifying Exigency

- Quid Pro Quo

- quota

- Racial Discrimination

- Racial Equality

- Racial Harassment

- Reasonable Accomodation

- Rebuttable Presumption

- Recess Appointment

- Reduction in Force

- Regarded As

- Regulatory Compliance

- Regulatory Enforcement

- Rehabilitation Act

- Religion

- Religious Accommodation

- Religious Discrimination

- Religiously Affiliated Employers

- Remote Working

- Removal

- Reporting

- Reporting Time Pay

- Reproductive Health

- Republican

- Request for Information

- Respondeat Superior

- Rest Breaks

- Rest Period

- Restaurants

- Restrictions

- Restrictive Covenant

- Retail

- Retaliation

- retaliatory termination

- Retina Scans

- return-to-work

- Rhode Island

- RICO

- RIF

- Right of Recall

- Right to Control

- Right-to-Work

- Rounding Policy

- Safety Programs

- Safety Sensitive Laborer

- Salaried Employees

- salary

- Salary History

- Salary Inquiries

- Salary Inquiry

- Salary Test

- San Francisco CA Minimum Wage

- San Francisco Parity in Pay Ordinance

- San Leandro CA Minimum Wage

- Santa Monica CA Minimum Wage

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act

- SCOTUS

- Seasonal Workers

- SEC

- Second Circuit Court of Appeals

- Secret Ballot

- Secretary of Labor

- Secretary Solis

- Section 7

- Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act

- Section 8

- Securities & Exchange Commission

- Securities Fraud

- Self Evaluations

- Separation Agreement

- Seperation

- Serious Health Condition

- Serious Violation

- Settlement Agreement

- Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals

- Severance

- Severe and Pervasive

- Sex Discrimination

- Sex Stereotyping

- Sex-Based Harassment

- sexual and reproductive health decisions

- Sexual Assault

- Sexual Harassment

- Sexual Orientation Discrimination

- Sexual Orientation-Based Harassment

- Shameless

- Short-Term Disability

- Sick Leave

- Similarly Situated

- Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals

- Social Media

- Social Media Policy

- Social Security

- South Dakota

- SOX

- Split Shift Pay

- SSA

- St. Paul Sick and Safe Time Ordinance

- St. Paul, Minnesota

- Stalking

- State Government

- Statute of Limitations

- Statutory Damages

- Statutory Exemption

- STD prevention

- Stock

- Stop WOKE Act

- Street Trade Permits

- strike

- Student Loans

- Students

- Subjectively Offensive

- Subpoena

- Substantial Relationship

- Successor Liability

- Supervisor Reassignment

- Supervisors

- Supervisory Employees

- Supplemental Wages

- Supreme Court of the United States

- Tax

- Tax Credits

- Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

- Tax Implications

- Tax Reform Act

- Teenage Labor

- Temporary Employee

- Temporary Help Agency

- Temporary Rule

- Temporary Schedule Change

- Temporary Workers

- Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals

- Termination

- Texas

- Texas Workforce Commission (TWC)

- Texting

- Third Circuit Court of Appeals

- Time Clock

- Time Records

- Tipped workers

- Title IX

- Title VII

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Tort Liability

- Trade Secrets

- Training

- Trans

- Transgender Rights

- Transitioning

- Transportation Industry

- Travel Time

- Trial

- Trump

- Trump Administration

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- U.S. Department of Labor

- Undergraduate Students

- Underrepresented Community

- Undocumented Workers

- Undue Hardship

- Unemployment

- Unemployment Benefits

- Unemployment Insurance Program Letter

- Unfair Labor Practice

- Union Dues

- Union Organizing

- Union Relations Privilege

- Unions

- Unit Clarification Petition

- Unlawful Employment Practice

- Unpaid Leave

- Unpaid Wages

- USCIS

- USERRA

- vacation

- Vacation Accrual

- Vacation Pay

- Vacation Policy

- Vaccination

- Vaccine Requirement

- VEBA

- Verdict

- Vested Rights

- Veteran Services

- Vicarious Liability

- Victims

- Violent Crime

- Virginia

- Voluntary

- Volunteer Programs

- Volunteering

- Volunteers

- Wage and Hour

- Wage Order 7

- Wage Order 9

- Wage Theft

- Wage Transparency

- Wages

- Waiting Period

- Waiver

- warehouse

- WARN Act

- Webinar

- Wellness

- Wellness Program Incentives

- Wellness Programs

- Westchester County

- WFEA

- Whistleblower

- White House

- Whole Foods

- Willful and Repeat

- Wis. Stat. ch. 102

- Wisconsin

- Wisconsin Court of Appeals

- Wisconsin Fair Employment Act

- Wisconsin's Wage Payment and Collection Laws

- Withdrawal Liability

- Withholdings

- Witness Statements

- Work Eligibility

- Work Permits

- Work Restriction

- Work Schedules

- Worker Classification

- Workers' Compensation

- Working Conditions

- Workplace Accommodation

- Workplace Bullying

- Workplace Discrimination

- Workplace Disputes

- Workplace Injury

- Workplace Injury Reporting

- workplace inspections

- Workplace Policies

- Workplace Rules

- Workplace Safety

- Workplace Training

- Wright Line

- written release procedures

- Wrongful Termination